With the snow squall sweeping Mexico-bound from Nunavut Land, the hiker paused to slip from his daypack, propping it atop a whitened, buckskin log. The log was remnant from an ages old wildfire that savaged the flanks of this mountain; indeed, that had raged through much of the Swiss-look-alike valley below.

The hiker shrugged from his down jacket, folded and stuffed it into the knapsack. Straightening to his slender six-foot height, the man pulled a big blue handkerchief from his jeans' pocket and carefully wiped beads of moisture from a pair of bottle-lens eyeglasses.

With the glasses back in place and vision restored, the man snatched off his stocking cap and, while turning a full 360 degrees, swiped the handkerchief across his forehead and beneath the collar of his denim shirt, all the while gazing in rapture at the full sweep of surrounding snowcapped mountains. How glorious to be alive! Especially in such a place.

He didn't yet know all their names, but he would. Martin and Deidre had told him the big one thrusting up from north of the lake, the lofty one with the exposed redrock shoulders, was Rising Wolf. And one of them mentioned Sinopah, too. He wondered why such a strange name should stick in his mind?

He watched a Park Service pickup tortoising along the macadam road far below, studied it for a moment, then turned to peer at the mountain to the west. Appistoki, Deidre had said. Still mostly snow-covered. He'd been told there would be mountain goats there. Hard to see white goats against white snow. The man dug into his daypack for a pair of battered binoculars, then swept the nearby open slopes for five minutes.

At last he grinned and shook his head. "Not yet. But if you're here, I'll spot you," he muttered. "And with luck, maybe I'll see a grizzly bear, too. Or," gazing down at a couple of beaver ponds near the lake, "maybe a moose." The man dropped the binocs back into his daypack, slung it, and, skirting a weeping snowbank, trudged on up the trail. He chuckled aloud while thinking of his new friends, how they'd promised to join him on today's hike but dropped out because of predictions of a spring storm. Because of them, he'd started late, not even leaving East Glacier until noon and not getting on the trail until an hour later.

Craig Dahl was twenty-six years old, in the prime of life and at the peak of his physical strength. With a degree in sports management, the young man was already a veteran outdoorsman, an accomplished hunter, angler, skier, canoeist, and backpacker. As such, he'd led canoe adventures in northern Minnesota and overnight hiking groups in Colorado's Rocky Mountains. Although new to Glacier National Park and the Northern Rockies, Dahl possessed a veteran outdoorsman's polished instinct for learning new landscapes, traveling new trails, riding new rivers, and spotting new wildlife.

He could read mountain weather, too. And, if he correctly read the dark clouds boiling over mountains to the west, the storm front wouldn't be long in arriving. A chill breeze began gusting around Craig Dahl.

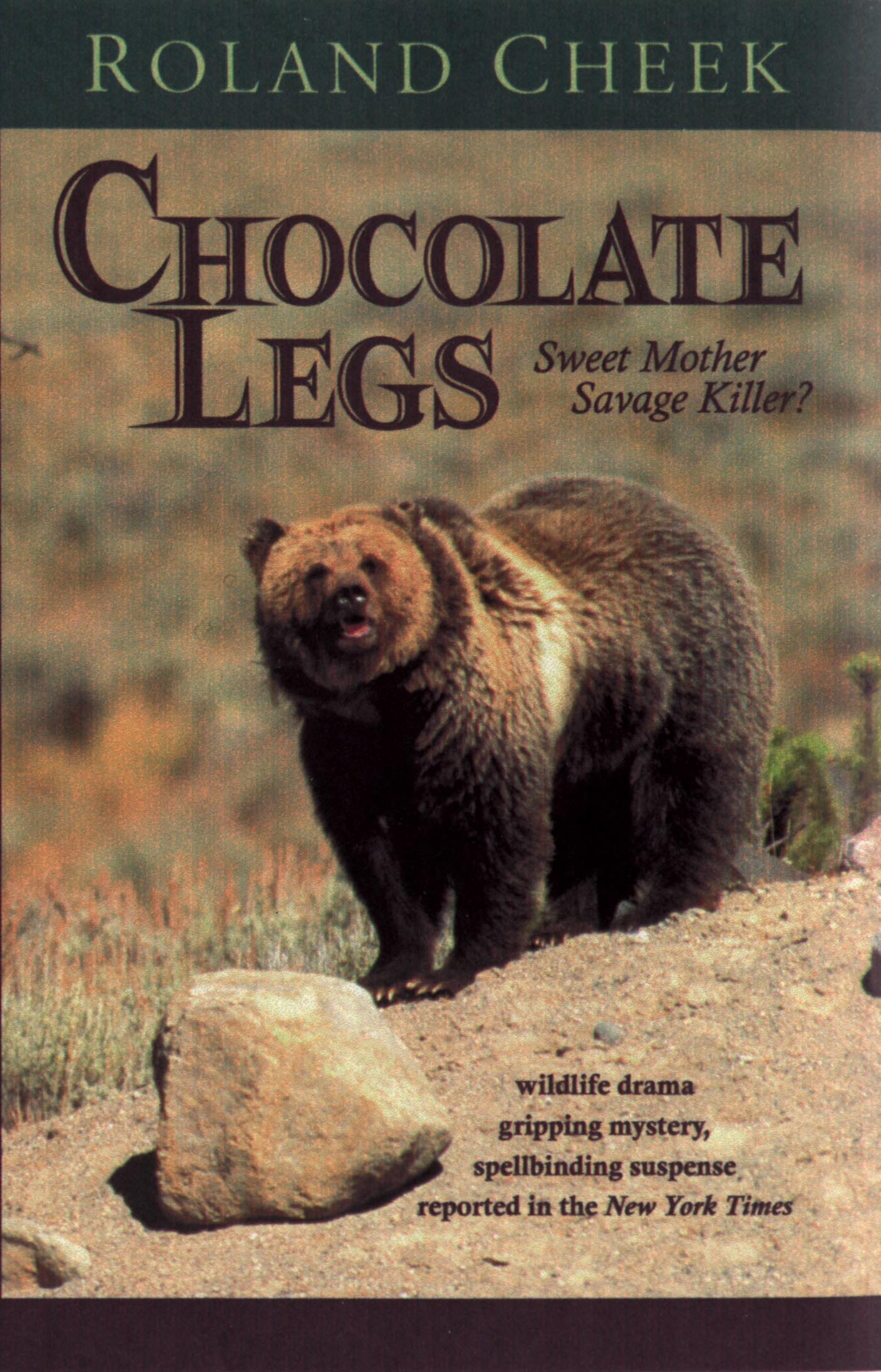

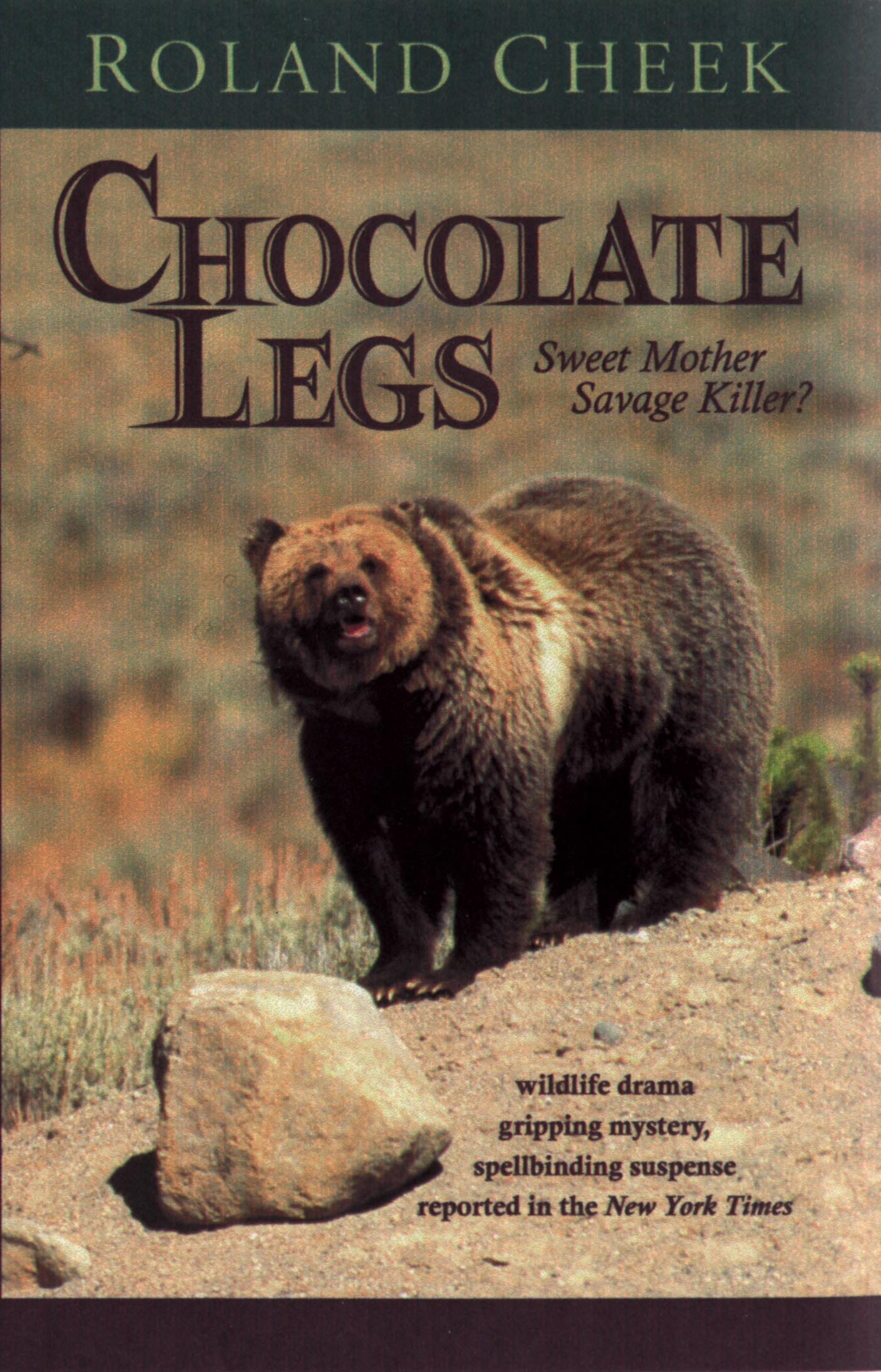

The bears knew of the man's presence long before the man knew of the bears. There were three: a sow and her brace of two-year-old cubs. They made a handsome family, Chocolate Legs and her two mirror-image offspring; each a classic blond shading to dark brown on their legsas if they'd just waded from a muddy marshand with raccoon-like masks around beady, penetrating black eyes.

The mother wore a fading yellow collar, nearly hidden by her still-thick winter coat. Though even more difficult to spot, she had aluminum tags clipped into each ear. The stocky young male cub sported a tag in only his left ear. The tags and collar were evidence the bears had at least some exposure to humans. Given the time (May 17, 1998) and their location (Two Medicine Valley, in Glacier National Park), that evidence suggested much more.

For several years, Glacier National Park has had a policy discouraging radio collaring of bears for research, holding that visitor experiences might be diminished by sighting animals wearing man-installed devices. Only in incidents involving risk to humans or occasionally to the animals themselves are bears trapped and relocated. In extremely rare occasions problem bears are fitted with radio collars and their movements monitored.

Though she and her offspring had become something of a nuisance around campgrounds and trails in the Two Medicine area, Chocolate Legs had not yet been deemed a sufficient problem for official action.

Not so outside the Park.

The boundary between Glacier National Park and the Blackfeet Reservation lies but three miles east of the Scenic Point Trail Craig Dahl hiked that day and where the bear family busied themselves digging for marmots and ground squirrels and early tubers. What's more to the point, the Blackfeet hold a jaundiced view of and a low tolerance for grizzly bears who invade campgrounds, demonstrate little respect for humans, and who ransack garbage cans, camp coolers, and food boxes. Thus the previous year, when Chocolate Legs and her brood entered the Red Eagle Campground, two miles into the Blackfeet Reservation, then ignored attempts by campers and management to haze them from the vicinity, the tribal office was alerted.

Chocolate Legs paused in pursuit of a hoary marmot and lifted her snout to the wind. The breeze was fickle and she soon returned to excavating football-sized rocks and pea gravel, thrusting her nose into the deepening hole and snorting, then once again digging furiously, stone and dirt spewing between her wide-spraddled hind legs.

A hundred feet up the hill and to the left, the blocky male pursued his own marmot with more enthusiasm and even less finesse than the mother. His more refined sister perched near her mother, watching intently should one of the beagle-sized ground hogs try to flee. She, too, lifted nostrils to the wind and whined. But her mother needed no warning. Again the sow paused. Yes, there! A man-smell.

In some ursid circles the scent would have been sufficient to send bears beelining for distant ridges. But not this bear. Not these bears. Instead Chocolate Legs stared down the mountain for a moment, then resumed her excavation. Above, her male offspring paused to peer down the hill at his mother and sister. He, too, had the human's odor. But, following his mother's lead, he resumed furious digging.

Soon, they heard the human's approach; first the clink of a rock, then the scuff of a boot. Next the "feel"the faintest of vibrations from the man's footsteps. The sow discontinued her digging to drift into a patch of head-high limber pines, the female cub crowding hard against her. The male cub made one more furious pass at his excavation, then galloped down the hill to join the two females. Standing as they were, it was apparent each of the two-year-olds were only a few inches shorter and half the heft of their mother.

Dark clouds nearly covered the heavens, leaving only a line of intense turquoise-blue to the east. Craig Dahl hurried to climb as high as he could before the storm broke. His head-down direction took him around the corpse of stunted trees, passing only a few scant feet from where three grizzly bears stood motionless against the mounting wind.

A few feet further and he came to another trail switchback and started to swing around it when something caught his eye. It looked as though a backhoe had been rooting around on the hill-side directly before him. He kicked at the dirt pile, wondered what had caused it, then turned and hiked on up-trail. Now his path led him away from the bears, back toward the point where he could look out into the valley. And Craig desperately wanted to see as much of the surrounding terrain as he could before he must turn for the parking lot and his car.

As the man tramped away, the sow stepped from her hiding place and peered after. The male leaped behind to whine and stare fixedly around his mother at the retreating man. The female cub whimpered in hunger and her sibling whined again and shuffled his feet. But the sow only stared until the man disappeared around the brow of the hill, then returned to work furiously at her marmot dig.

Ten minutes later, the man popped out on a trail switchback far above, where he shrugged off his backpack, and pulled out and slipped into his windbreaker. While doing so, his thoughts returned to the strange excavations he had seen far below. Leaning into the rising, howling gale, he resumed his climb.

A half-hour later, the storm broke about him rain mixed with snow and Craig Dahl knew he would not make Scenic Point. Nor, even if he did, would he enjoy what he was told was one of the most fabulous vistas in Glacier Park. Even from here his view into the valley below was gone. Shrugging at the fickleness of fate, the man turned to head back the way he'd come.

Traveling downhill was easier and with thoughts of the warm car and hot coffee driving him, his strides were mammoth, the passage swift.

Snow mixed with rain squalled all about him, fogging his glasses. Dahl laughed aloud at thought of how he needed windshield wipers and defrosters. Then his mind turned to the long drive back to his room and bed, and the new job he'd begun only a couple of days before.

Soon Craig Dahl reached the level of the strange excavations. He paused to stare curiously at the one nearest the trail. If anything, the wind was picking up intensity and an eerie keening swept through the thick and windswept waist-high trees called krummhulz he'd heard. He bowed his head into the biting, driving rain and snow and deliberately wiped a finger across the right lens of his eyeglasses. Then he took a step toward the mounds of dirt, and the krummhulz beyond.